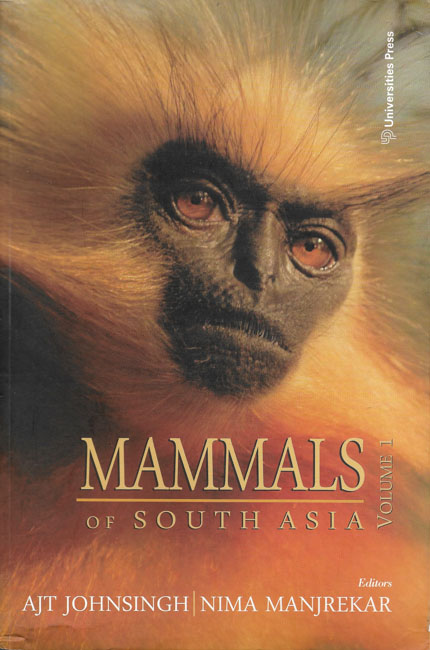

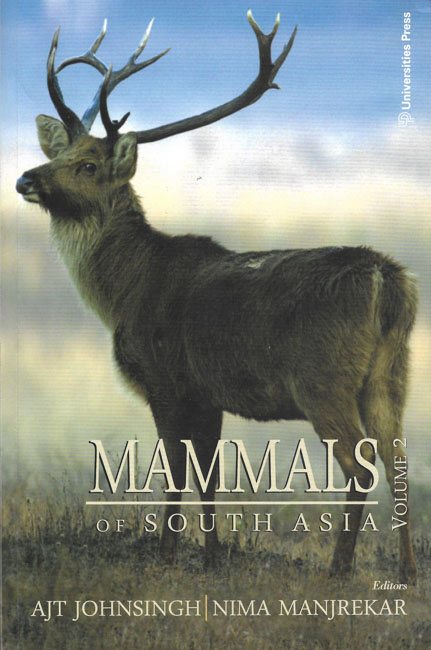

Book Review: Mammals of South Asia

Editors AJT Johnsingh, Nima Manjrekar

The Indian subcontinent, which is home to more than 1/6th of world’s population, is also rich in its natural heritage. However, leave apart laymen, even nature enthusiasts would be stunned to learn that South Asia is home to 574 species of mammals. There have been books in the past to describe some of the major mammals of India like A Dunbar Brander’s Wild Animals in Central India (http://www.indiawilds.com/diary/wild-animals-in-central-india/ ), RI Pocock’s Mammalia on Primates, SH Prater’s The Book of Indian Animals and recently Vivek Menon’s Indian Mammals-A field Guide (http://www.indiawilds.com/diary/indian-mammals-%E2%80%8B%E2%80%8Ba-field-guide/) etc. These were excellent efforts and had solved the purpose during the times they were written. Many of us have learnt a lot from these books. Nevertheless, when I came to know that a new book Mammals of South Asia has been published in two volumes, I immediately went ahead and bought a copy, as these two volumes cover updated information based on various research studies.

Mammals of South Asia is edited by Dr. AJT Johnsingh and Nima Manjrekar and spans across two volumes and contains articles by various researchers. A total of 87 authors have written the chapters in the two volumes with 46 of them contributing to the first volume. Dr. Johnsingh says that he worked on this book between 1996 till 2005 during his WII (Wildlife Institute of India) days. Only such an exhaustive effort, unthinkable unless someone is really determined, could do justice to the huge number of species found in South Asia as well as to filter out and include key elements from the lot of research efforts being carried out by many biologists.

The Mammals of South Asia (Vol. 1 and Vol. 2) are treasure troves of information and will not only appeal to the researchers but will also appeal to naturalists and layman. There are various tables displaying data neatly and will be of value to serious scholars as well as the layman. For eg. one can realise that out of 137 endemic species found in the South Asian region, 51 (37.23%) belong to India. This can make one think of protecting these species, as the endemic species are found nowhere else and loss of their habitat or any other survival challenge can simply wipe them out from the face of earth.

The volume one contains the mammals belonging to the Order: Insectivora, Scadentia, Chiroptera, Primates and Carnivora. And the volume two contains the orders (Cetacea, Sirenia), Proboscidea, Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla and Rodentia.

Since these two volumes are exhaustive, some people may just brand them as reference material and keep it in the shelf. However, I find these two books extremely readable and some of the information will definitely arouse curiosity of people.

Did you know this?

Indian Fox:

Did you know that the Indian fox is not strictly a carnivore and feeds on fruits and other vegetable matter?

“Amongst vegetable matter, the Indian fox has been reported to feed on fruits of ber (zizyphus sp.), neem (Azadirachta indica), mango (mangifera indica), jambu (Syzygium cumini), banyan (Ficus bengalensis), melons, and the shoots and pods of Cicer arietum (Mivart 1890, Prater 1971, Mitchell 1977, Roberts 1977, Johnsingh 1978, Manakadan and Rahmani 2000, Home and Jhala 2009).” (page 359, Vol. 1)

Indian Fox

Golden Jackal:

Did you know that jackals have the intelligence to store food for future?

“Jackals have the habit of caching extra food by burying it (Kingdon 1989)…. A lot of vegetable matter features in the diet of jackals; during the fruiting season, they feed extensively on the fruits of the Zizyphus sp., Carissa carandas, Syzygium cumini, and pods of Prosopis juliflora and Cassia fistula (Kotwal et al. 1991)” (page 370, Vol. 1)

Wolves:

Wolves have a sinister reputation. They have been characterised malevolently in many myths. So you would be surprised to read this:

“Wolves also eat locusts, other insects, reptiles, birds, and vegetable matter like the pods of Prosopis juliflora and fruits of Zizyphus sp. (Sharma 1978, Jhala 1993a)”. (page 382, Vol. 1)

Wolf

There are also many more interesting aspects of various species described in the Mammals of South Asia.

Different Soldier & Police in Nilgiri Langurs:

“The adult male dominance hierarchy was a relatively rigid and well-defined order, which was maintained with minimal aggression. Most male-male dominance interactions were accomplished in a non-violent manner through visual cues. In a typical sequence, the dominant male simply looked at the subordinate animal, which usually responded by looking away. This promptly terminated the interaction”. (Page 245, Vol. 1)

How nice it would be if we humans too looked the other way when someone is angry, rather than get engaged in fisticuffs?

Also the book has very interesting information on the Alpha male. “the alpha male was not the largest animal, nor did he possess large canines. He played a major role defending the troop during inter-troop altercations and territorial battles, but did not actively intervene in intra-troop disputes. The alpha male was involved in more dominance sequences than other males. Although he expressed his dominance rarely, he was the most active animal in inter-troop dominance interactions. He had greater freedom of movement and choice than other individuals, and troop activity was patterned after the alpha male.” (page 245, Vol. 1)

If we try to find a similarity between human society and the nilgiri langurs, it is like the biggest bodybuilder is not the one who fights in the frontlines in the army. Ability and attitude trumps bulk. Also, the alpha male who leads the troop in battle against outsiders doesn’t do police duties. May be if our Government can learn a thing or two from these Nilgiri langurs and stop using the Army in domestic strife, a long pending demand of our Army be met and they remain out of petty local politics.

As far as interaction of Nilgiri Langur with Lion-tailed macaque is concerned it is mentioned that “Interactions between the two species can be mildly agonistic. During most observed encounters, the macaques often displace the langurs”. (page 248, Vol. 1)

However, Dr. Ajith Kumar, the author of this article has mentioned in a different publication (IN DANGER, Indian Wildlife and Habitat) about fights between these two species and also one instance of a Lion-tailed Macaque killing a Nilgiri langur infant and not eating it. “As the lion-tailed macaque is a fruit eater and the Nilgiri langur, a leaf eater, they seldom fought over food. Instead, fighting often started when they came together on the same tree and an infant or juvenile of either species felt threatened by the other species. The adults would immediately join in kicking up a fight. Often the fight ended quickly after an exchange of growls, and with the Nilgiri langur retreating. One day, however, the fight became particularly intense with the adults chasing each other…..within seconds, the (Lion-tailed macaque) male was going up the same tree but with a Nilgiri langur infant clutched in his mouth. While other monkeys growled and wailed even more excitedly, he went up about five metres, stood with the infant in his mouth for a couple of minutes, then dropped it to the ground”. (IN DANGER, Indian Wildlife and Habitat, edited by Paola Manfredi, page 100) Since this observation adds another dimension to the Nilgiri langur’s conflict, it could have also been added to the book.

Redirected Aggression in Rhesus macaque:

Rhesus macaques have a very close association with humans as they live in “a wide variety of habitats, including cities, villages, farms, forests, semi-deserts and mangrove swamps”. (page 138) In the dominance behaviour of Rhesus macaque: “Often when threatened by a dominant, subordinates redirect their aggression by threatening lower ranking individuals (Srivastava 1999)”. (page 142, Vol. 1)

Whether the monkeys learnt this behaviour due to their close association with humans or the humans learnt this from these macaques is not known.

One interesting behaviour is the mourning of the dead. “Around human habitation and temple sites in India, ‘urban’ macaques die of electrocution and in road accidents more often than any other cause. After the death of an infant, the mother may carry the corpse for several hours to several days, even after it starts decaying”. (page 144, Vol. 1)

Hoolock Gibbons can sing:

“The adult hoolock gibbon pair produces a loud and elaborate song in the form of a duet, in which juveniles and young may join in. The song comprises an introductory sequence, an organising sequence and a great call sequence. The adult male and female sit close together while singing and break into vigorous swinging displays as the great call sequence rises to a climax… Solitary females have been heard singing solo, but either of a mated pair will not call alone.” (page 343)

Musk Deers:

Did you know that Musk deers are not true deers? The Musk deer (Moschus spp.) are small forest ruminants and they differ from other deer in not having antlers and facial glands. “They have a gall bladder, caudal gland and musk gland, which other deer do not possess. They have only one pair of teats, wheras other deer have two. the upper canines are greatly developed in musk deer, especially in males. In females, the upper canines are small and never protrude below the lip of the lower jaw. Therefore, musk deer are not true deer, but deer-like ruminants… Hassanin and Douzery (2003) placed the Moschidae firmly as sister to Bovidae, based on mitochondrial and molecuarl sequences”. (page 159, Vol. 2)

Also, did you know that “as an anti-inflammatory agent, musk is a more effective antidote for snake venom than hydrocortisone”. (Page 172, Vol. 2)

Asian Elephant:

Did you know that “the living elephants are the descendants of a fairly small tapir-like mammal, Moeritherium, that lived at least 45 million years ago, and whose fossil remains were first described from Lake Moeris in Egypt in 1904 (Delort 1990)” (Page 71, Vol. 2)

“The Gajasastra attributed to Palakapya (sixth to fifth century BC) mentions the presence of elephants in almost the whole of India, including the present states of Rajasthan, Punjab, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, from which they have now disappeared.” (Page 72, Vol. 2)

Only 30 percent of elephant habitat is protected: “In 2000, estimates of wild Asian elephant population ranged between 34,000 and 50,000 animals, with their habitat covering an area of about 439,000 sq km, of which only about 132,000 s km (30 percent) is protected (Kemf and Santiapillai 2000). Data of this nature are classified as Informed Guesses. However, even these optimistic estimates show that the total population of the Asian elephant is only 10 per cent of the current estimate for the African elephant population and has declined in the majority of the range countries; this seems logical because there has been a precipitous decline in available habitat across the elephant range, barring southern India.” (Page 72 & 75, Vol. 2)

Speed of an Elephant: “Walking gait is about 6.5km/h and a charge may reach a speed of over 48 km/h (Scott 1973). The tail is used to drive away biting insects and at times for scratching. When alarmed, elephants often run holding their tails up, which may serve as a signal to other herd members of imminent danger.” (Page 76, Vol. 2)

Rhinoceros:

Did you know that Javan and Sumatran rhinoceros at one time roamed in India? The Indian rhinoceros, “is the largest of the three extant species of rhinoceroses found in Asia, the other two being the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus) and the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), both of which have been extirpated from northeast India.

The family to which the greater one-horned rhinoceros belongs, the Rhinocerotidae, flourished in the Oligocene after first appearing in the late Eocene in Eurasia. (page 95, Vol. 2)

Reduced size dimorphism: Male and female rhinos look similar with slight size difference. “Among free-ranging rhinos, adult males are essentially a slightly larger version of females. The most conspicuous differences in morphometrics are directly related to the dental weapons and the enlarged neck and shoulder musculature of males, relied upon during the frequent inter-male fights that determine dominance and access to estrous females. Reduced size dimorphism in free-ranging animals may be explained by greater stress on males, and poor nutrition during the long non-breeding interval when young adults are harassed by dominant males and excluded from prime grazing areas.”

There are many more interesting information about various species, than I can reproduce here. George Schaller writing in the foreword of these two volumes says that “the two volumes cover all 590 species in the region, many of them in detail and depth, based on consummate research conducted during the past half-century. This reflects a genuine increase in knowledge since the 1960s; when many species- from slender loris to elephant – were, for the first time, studied in the wild by trained biologists, with patience and respect, to create intimate and enduring portraits of other beings”.

Frankly speaking there is so much of information in these two volumes that I think to digest those and then go out in the field and observe those behaviours will take several lifetimes. It may be pertinent to remind our readers that some of these authors have spent better part of their careers studying the species and these chapters succinctly describe those observations. It is actually a very humbling feeling to hold these two volumes in hand and feel how less I know.

Published by Universities Press, the Mammals of South Asia, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 are now available in amazon.in at a steeply discounted price of Rs.1061/- and Rs. 1096/- respectively. Now the kindle editions are also available, so reference in the field is also easier. I would unhesitatingly recommend these two volumes for all wildlife enthusiasts, researchers, naturalists, wildlife photographers and filmmakers, policy makers, students and teachers.

Must buy!

Click on the link below to order on amazon –

- GoPro Hero 12 Black - 6 September,2023

- Leopards: The Last Stand - 2 July,2023

- Drifting in the Waters of Sundarbans - 26 March,2023