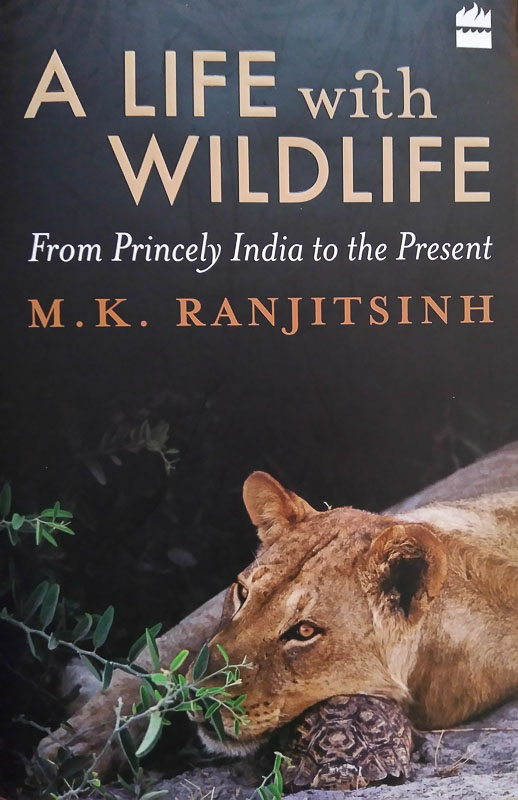

Book Review: A Life with Wildlife – From Princely India to the Present

By M. K. Ranjitsinh

M. K. Ranjitsinh’s book “A Life with Wildlife – From Princely India to the Present” is a fascinating book and is thoroughly educational. Written in a first person account with the author as the protagonist, documenting the events happening around him from his Childhood in the Princely state of Wankaner to his working in the Government of India and UNEP and then post-retirement innings outside the Government trying to save Wild India, this book is lucidly written and also contains lot of gems that should be brought infront of the readers.

The author belongs to the Princely family of Wankaner in Gujarat and hence was a witness to some fascinating wildlife shoots as well as conservation actions undertaken by various princely states. In the book he theorises that mostly the rules of Princely states used to take interest in wildlife if they were keen hunters. And being hunters they used to preserve the wildlife solely for their hunts and hence the wildlife got preserved. He gives an example of Kashmir, where the rulers were not interested in hunting but the British agents were keen hunters and took action to preserve the wildlife.

He also gives an account of how a leopard family was enticed from Rampara to Gadhia Hills, a distance of 9 kms straight. Without the benefit of technology to tranquilise and shift, it is indeed a learning for the present generation to understand how they could bait and progressively move the leopard a few hundred meters at a time and make them completely shift to Gadhia hills. “The technique was to lay a bait every third day some 300 meters further along the direction they wanted the leopard to move. In Foshido, they allowed the animal to settle for a week and then started shifting the bait towards Gadhia. As that involved traversing open fields, a frequented road and a railway line, the distance between the sequential baits was reduced to about 200 meters. The entire process of bringing that male leopard from Rampara to Gadhia took a little over two months. Once there, he was fed intermittently. Then he disappeared for about ten days and returned with a female. After that, there was a permanent leopard population in the Gadhia hills of not less than three adults and going up to seven, including cubs, for the next forty years, until 1952.”

In some of the Chapters the author quotes from his notes about his visits to various wilderness areas in India as well abroad and it gives us a rich understanding of the wildlife in those days. I am sure some of us would ask God as to why we were not born in such an era, when wildlife was “numerous” or “plenty” and jungles were pristine as opposed to the polluted mess that our rivers and forests have become with more people visible in forests than wildlife.

The author being in the Indian Administrative Service and dealing in wildlife, gives us a first hand account of the brush of wildlife with extinction and the way Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister’s role in saving our Wilderness and Wildlife by creating legislations that have become the hallmark of Conservation in India. It is another matter that present day Governments are less concerned with the preservation of wilderness and wildlife and more about their votebanks and other material interests.

The author recounts that in September 1971, Mrs. Indira Gandhi had called for a meeting to discuss the declining wildlife in the country. At that time Wildlife was a State subject. During the meeting by Billy Arjan Singh had asked “What priority does wildlife have in your scheme of things, Madam prime minister?” That kind of criticism is unthinkable these days and is a sure shot way for the person to invite the iron hand of the Government machinery. After Billy had spoken Mrs. Gandhi had asked “So what can be done for wildlife?” Ranjitsinh writes that on being prompted to speak he said “There was no uniform legislation for wildlife protection in the country. The provisions of the Indian Forest Act, 1927, under which the states operated, only dealt with hunting and the issuance of licences for this purpose. Maharashtra and a couple of other states had better laws of their own, but these too were inadequate. India needed a comprehensive wildlife legislation that would be uniformly applicable to the country and would actually address the protection of species and their habitats, the creation and management of protected areas, the control of wildlife trade and taxidermy and the rest. I went on to add that though the subject of forests and wildlife was in the State List under our Constitution, the Central Government could legislate on a state subject under the provisions of Article 252, whereby if two states of the Indian Union passed a resolution in their respective state assemblies approving of a legislation on a state subject to be passed by the Central Government, parliament could pass such a law. It would apply to those two states and subsequently to others who adopted it by a similar process, after its passage in parliament.” Karan Singh had asked which states would surrender their constitutional rights. “I will ask the states to give us such a mandate” replied Mrs. Indira Gandhi in a low, clear voice. (Page 112-113)

This shows the commitment of Indira Gandhi towards the welfare of Wildlife as well as understanding the importance of our natural heritage. It also showed her leadership skills and statesmanship, a trait which is rarely in display these days by our politicians and bureaucrats.

In another interesting anecdote from Indira’s India perhaps tells us the impact of wilderness areas on us and India’s former PM Mrs. Indira Gandhi. “Her Congress party had been totally routed in the election of 1977 and she had lost her seat in parliament. Under the new Janata Government, she was arrested for her role in the Emergency and was being taken in custody, to the Sultanpur Bird Sanctuary near Delhi. This was ironic, as Sultanpur had become a sanctuary mainly at the instance of Indira Gandhi. A railway line had to be crossed for the motorcade to reach Sultanpur and as a train was approaching, the gates of the railway crossing were closed. Indira Gandhi was allowed out of her car and she went and sat on the parapet of a culvert, very dejected and depressed. She was very soon recognised, a crowd collected and people began calling out her name and cheering. The officials who were with her say her demeanour changed as she realised that she was not a total national reject, that some segments still admired her. By the time she reached Sultanpur, she apparently was a different person and the old grit to fight back was returning. Did the road to a wildlife sanctuary pave the way for her return to power?” (Page 157)

In the same chapter Indira’s India, M. K. Ranjitsinh gives another fascinating story of how Eravikulam National Park and Rajamala Sanctuary were declared. KDHP (Kannan Devan Hills Plantations Pvt. Ltd.) had got the land on lease from the Raja of Cochin. They had converted some portion of it into tea plantations and were preserving the “Nilgiri tahr on the uplands of the Rajamala-Eravikulam massif in the Kerala High Range, the highest point in the Western Ghats…the upper range of Eravikulam and the adjacent Rajamala ridge in the Kerala High Rage contain perhaps the most pristine ecosystem in India south of the Himalaya.” In 1971 the Kerala Government revoked the landlease on the pretext that some portions have never been cultivated and it violated the lease terms. The idea was to distribute the land to the landless in sync with the ruling Communist Party of India’s principles. The author writes that he tried to convince the Kerala forest minister Baby John, who was ironically over 6 feet tall, about the folly of attempting to cultivate the Eravikulam-Rajamala area due to their inhospitable climate and very thin top soil. The minister was unmoved. Later a very fortunate occasion presented itself when the same minister Baby John was to meet the Union Minister of Food and Agriculture Annasaheb Shinde, who at that time was also temporarily holding charge of forests and wildlife. Kerala was under severe drought and its Minister Baby John wanted rice for his state. And a unique bartering deal started where Annasaheb Shinde promised 25 wagons of rice in lieu of declaration of national park. “The negotiation went on in a very civil way – tahr in lieu of rice. The deal was ultimately settled at thirty-six wagons of rice for the declaration of Eravikulam National Park and Rajamala Sanctuary; part of the quantum to be released immediately, the rest after the declaration of the protected areas. Today, this barter sounds like a fairy tale. But it did happen.” (Page 132-133)

The above story also tells us that if a bureaucrat wants to make things happen and perseveres, then he/she is likely to find an opportunity to bring the unique powers of the Government into play. Some imagination, creativity and perseverance goes a long way.

In the Chapter Bhopal, Gas and Union Carbide the author writes:

“Natural disasters do occur and the early warning and response systems often fall short of the requirement. But the real lesson of Bhopal, I feel, has not been understood, let alone learnt. And that is, do we really need a pesticide as lethal as Sevin? That pesticides kill agricultural pests and, thus, increase productivity is undoubtedly true, but in a real cost-benefit analysis does that truly compensate for the toxic poisons that will permeate our food chain? And when these agricultural pests get immune to even these highly toxic chemicals, just as human pathogens are becoming resistant to antibiotics, do we resort to making those pesticides more and more deadly, for both the pest and for man? Is short-term productivity more important than the long-term health of the nation?

It is a little known fact that at the time of the Bhopal incident, the Central Insecticides Board and Registration Committee of the Government of India was considering the banning of Sevin and twenty-four other highly toxic pesticides. Why did they hesitate? Lobbying from the manufacturers? Fear of a reduction in cereal yield? The Ministry of Agriculture banned the production of DDT for agricultural purposes, as it did diclofenac much later. But the production and use of DDT for anti-malaria spraying is still permitted and India still produces, perhaps, the highest quantum of DDT in the world? Why? To keep the DDT factories running? Are we even planning for organic or other substitutes that would, perhaps, not be so effective but would also not be so harmful? What are the ground rules of a genuine cost-benefit analysis and who decides? When will the people of India be consulted and given a choice?” (Page 232-233)

“The Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972, had provided for special hunting licenses for the shooting of some species of birds and animals. In that era when the hunting ethos still prevailed, the maximum we could achieve was a complete ban on all endangered and threatened species, with some outlets for the then powerful hunting lobby, mainly the shooting of migratory birds. the scenario had since changed in the intervening two decades, with the conservation ethos having spread throughout the country . so when I discussed with Maneka Gandhi the amendments to the Wild Life (Protection) Act, which were due and which I was handling, she insisted on the deletion of all hunting licences, and rightly so. On 2nd October 1991, Mahatma Gandhi’s birth anniversary, a major amendment of the Wild Life (Protection) Act came into operation….All hunting was prohibited, barring the destruction of specific vermin in specified areas, and for research and scientific purposes.” (Page 263-264)

Alas, Maneka Gandhi at that time would not have known that a two decades and half later the Union Government and the State Governments will wage a war on wildlife using the loophole of “specific vermin in specified areas”. So Nilgai, wild boar, monkey, deers and even elephants are being wiped out. Tigers and Leopards are routinely killed by the forest department inviting a few specific killers who proudly post the photos of slain tigers and leopards under their feet.

M. K. Ranjitsinh belonged to the Madhya Pradesh cadre and it is amazing that he could create 14 sanctuaries and 8 national parks, which later became 9 National Parks. He writes “I had been adopting a risky modus operandi, deciding with Chief Wildlife Warden J. J. Dutta the boundaries of national parks and sanctuaries and notifying them in the state gazette, and only thereafter informing the forest minister and the chief minister of the establishment of the protected area. After the imbroglio over the naming of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, I took care to not even mention our intention of declaring a protected area to anyone until after it was notified. Also, the finance department was not kept informed in advance, as the stoppage of forestry operations pursuant on these declarations of protected areas meant a loss in annual revenue. We knew that if we sought the concurrence of the finance department, we would perhaps never get it. We were saved by the fact that there was no lessening of the total annual revenue of the forest department. The price of good timber was rising annually and as the stoppage of forest extraction happened in the protected area, the auction prices of harvested timber consequently went up in the neighbouring forests, following the age-old equation of demand and supply.” (Page 197)

“By now I had been forest, tourism and sports secretary in MP for two-and-a-half years. when I had taken charge, there were three national parks with a total area of 2,144 sq. km and twenty sanctuaries with a total area of 4,612 sq. km in the state, which then included Chhattisgarh. During my tenure, eight new national parks were added which have now become nine with the splitting of the Sanjay National Park. Of the existing parks, the area of Bandhavgarh had been more than quadrupled and Madhav National Park more than doubled, and there was a total addition of 5,592 sq. km to the coverage under national parks. Fourteen new wildlife sanctuaries had also been created during this period and three existing sanctuaries were extended. From 1983 till today, MP has added (only) two new sanctuaries and Chhattishgarh one, an addition of a total area of 233 sq. km.” (Page 211).

This stunning statistics shows what one determined individual can create. If not for a person like M. K. Ranjitsinh doing his job, our country would have been poorer as most of the areas he helped protect by notifying them as National Parks and sanctuaries would have been decimated without such protection. The barasingha in Madhya Pradesh would have been decimated as well.

M. K. Ranjitsinh’s “ A Life with Wildlife – from Princely India to the Present” is a book worth reading and re-reading as one can get inspired from his actions. Scholars as well as laymen, naturalists, wildlife aficionados, policy makers, historians, teachers, students and everyone in between can benefit from this book and can understand how the fortunes of our wildlife transitioned from under the british rule to the current rulers. This hard bound book published by Harper Collins is divided into 14 chapters and has 380 pages. Priced at Rs. 799/- it is available at only Rs. 499/- in amazon. We unhesitatingly highly recommend this book.

Highly Recommended.

- GoPro Hero 12 Black - 6 September,2023

- Leopards: The Last Stand - 2 July,2023

- Drifting in the Waters of Sundarbans - 26 March,2023